Political Cartoon - "Bush Blasts Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty" by Peter Nicholson

"Which Countries Have Nuclear Weapons?" BBC News. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 Dec. 2014

Statistical Map - BBC; Federation of American Scientists

"Which Countries Have Nuclear Weapons?" BBC News. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 Dec. 2014

Magazine Article - Forbes

The Nuclear Weapons States - Who Has Them And How Many

POSTED: 9/25/2014 @ 10:54AM

Nuclear energy is growing around the world. About 70 new reactors are under construction worldwide (NEI), with more than 600 others planned by mid-century. Five reactors are under construction in the United States.

On the other hand, nuclear weapon states have declined slightly in the last twenty-five years (see figure below). Several old players have dropped their nuclear weapons programs or given their weapons back to Russia, including South Africa, Kazakhstan, Belarus and the Ukraine. The latter now regrets that decision very much.

But since 1990, only two new players have succeeded in developing nuclear weapons, Pakistan and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (the DPRK, formerly known as North Korea). And only because a very clever Pakistani scientist named Abdul Qadeer Khan who developed Pakistan’s weapons program and sold stolen nuclear secrets to Iran, the DPRK and Libya.

Iran was threatening to enter the weapons club, but they are now unlikely to complete the final steps. Libya abandoned its weapons program under pressure from the U.S. after failing to make real progress, and has since become a failed state. Syria tried to secretly build a weapons reactor at al-Kibar with DPRK’s help several years ago, cleverly disguised as a 10th century Byzantine fortress (see figure below), but the Israelis bombed it before it got started, a fortunate move given the subsequent civil war in that country.

Therefore, the focus on weapons proliferation by the United States and the International Atomic Energy Agency has been diligent and pretty effective. This simple discussion cannot cover the total complexity of this issue, and more can be found at Stanford’s Nuclear Risk Group, especially the work by Dr. Hecker.

Presently, there are nine nuclear weapons states with about 10,000 weapons, down dramatically from the 100,000 at the height of the Cold War:

Russia 5,000 U.S. 4,400 France 290

China 240 U.K. 195 Israel 80

Pakistan 200 India 150 DPRK ~ 6

In contrast, there are 430 commercial nuclear reactors in 31 countries, assuming 10 or so in Japan are closed permanently and Germany permanently ends its nuclear program (see figure above).

No nuclear weapons program ever came out of a nuclear energy program. It is theoretically possible, but not practical. Nations have tried, but even Argentina and Pakistan realized that if you want weapons, you develop a weapons program and pick one of the two traditional paths to the bomb. And no one is fooled by an energy front.

In fact, those countries that have the bomb developed weapons programs for that very purpose, regardless of whether they had a nuclear energy program or not.

The connection between energy and weapons is that nuclear energy states have some of the basic knowledge and some of the infrastructure to start a weapons program, but only if they decide to obtain or develop the rest of the infrastructure and knowledge (see top figure). The time required for them to produce a bomb, after they make this momentous decision, and then successfully test it, is termed the latency period (Sagan 2010).

As examples, Peru has no nuclear energy or nuclear infrastructure of any kind and so doesn’t have a latency period. Sweden has nuclear energy but insufficient infrastructure to make a weapon in less than about five years, so its latency period is about five years. Iran’s latency period is about 6 months. Through political negotiation and economic pressure, they are now not expected to pursue the final steps to a weapon. But their latency period will likely always be less than a year.

Pu and U

An atomic bomb is a containerized uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction that can be made from either U-235 and Pu-239, or both, the two elements that can be easily split apart to release a lot of energy. Since a reliable and effective bomb requires each element to be pretty pure (over 90% of either U-235 or Pu-239), one needs to choose the specific path for each.

For a U-bomb you can depend on, you just need to enrich the U-235 up to about 90%, way more then the 3% to 5% for a commercial reactor. However, in addition to needing many highly sophisticated centrifuges and associated technologies, it takes a lot of energy to enrich U-235 to weapons grade, a lot of electricity to spin that many centrifuges that fast.

To weaponize U, it’s easiest to make a big gun assembly (see figure above), put two separate globs of U-235 not large enough to go critical alone, something like 40 lbs each but when combined is more than enough, pack propellant or explosives behind one of them, and at the right moment propel it into the other so it goes critical. This is the easiest way to make an atomic bomb.

It was so easy, we didn’t even have to test it in 1945 before we used it.

For a Pu-bomb, you need a weapons reactor to produce enough Pu-239, which needs to be separated from the other elements. To weaponize it, you need to make an implosion assembly (see figure above), put a smaller glob of Pu-239, only 15 to 20 lbs since Pu-239 fissions better than U-235, but that is not dense enough to go critical. Then pack high explosives around it so that when they explode, the Pu is compressed to super high density and goes critical.

An implosion-type Pu-bomb is a lot more difficult to make than a gun-type U-bomb and we were uncertain enough about it working that we decided to make two Pu-bombs so we could test one at the Trinity Site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945 before we used the other one on August 9th.

So a U-bomb is easier to make, but a Pu-bomb is better to have tactically.

This choice between U and Pu is reflected in the weapons programs of Iran and the DPRK. Iran decided to build a U-bomb to threaten its regional neighbors and to counter Israeli’s atomic weapons. They were never wanting to threaten the world. they also have significant uranium deposits.

Iran was using centrifuges to highly-enrich U, and got up to about 20% U-235. They did not require a weapons reactor. In fact, Iran recently completed and fired up a commercial power reactor, started with Russian fuel, and no one gave it a second thought since that is not a path to a weapon.

However, Iran is now blending down its highly-enriched U-235 stocks, and is not expected to complete the steps needed to make a bomb. They will continue to enrich to fuel levels, depending upon the final agreements reached, and hopefully will take this opportunity to turn their enrichment capabilities to commercial use in producing low-enriched fuel for the region’s growing commercial nuclear programs.

On the other hand, the DPRK went for the Pu-bomb because they don’t have a lot of electricity generation, and a Pu-bomb is lighter and easier to put on missiles since they actually want to threaten the world. They built a weapons reactor, that couldn’t make energy even if they wanted it to, but that was designed specifically to produce Pu-239.

They reprocessed the fuel (see reprocessing figure in the previous post), and built an implosion-type Pu-bomb. They successfully built and tested two devices, and have enough Pu to build several more.

Note – Iran may be also be pursuing the Pu route. They are completing a 40 MW heavy-water moderated reactor at Arak, ostensibly for research and isotope production, but that could be used for Pu production to pursue this other path to a weapon, particularly one that can go on a missile. It would not surprise me if Israel is watching this heavy water reactor closely with an eye to bomb it before it gets going, just like they did in Syria.

But what about the large amount of U and Pu that has been produced by the United States, Russia and other nations over the last 70 years? A fair amount of weapon grade U and Pu around the world is not in bombs, something like 2,000 tons, enough to make thousands of bombs (Dod Readiness Through Awareness). It is a little frightening to know that some of it may not be well-secured, but the United States and the United Nations are working to secure them and seem to be making good progress.

Finally, there are fusion bombs, or thermonuclear devices. These nuclear weapons, made from fusing hydrogen into helium, are much larger and hundreds of times more powerful than atomic bombs made fromfissioning heavy elements into pieces as we’ve been discussing. Fusion bombs do require a small fission-bomb trigger, however, to initiate the second stage fusion reactions.

Fusion bombs are so difficult to make, require such large sophisticated facilities, huge nuclear workforces and enormous amounts of money, that only the most advanced nations have developed them, such as the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China. India tried but failed, although they claim to have succeeded. We aren’t worried about anyone new like the DPRK making fusion bombs. We’re worried about them making atomic bombs which are more than enough to get respect from one’s neighbors and strike fear into everyone else.

After all, blowing up the world ten times over was a fusion fantasy of the Cold War.

"The Nuclear Weapons States - Who Has Them And How Many." Forbes. Forbes Magazine, n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2014.

Song - "Who's Next" by Tom Lehrer

Who's Next

by Tom Lehrer, 1967

First we got the bomb, and that was good,

'Cause we love peace and motherhood.

Then Russia got the bomb, but that's okay,

'Cause the balance of power's maintained that way.

Who's next?

France got the bomb, but don't you grieve,

'Cause they're on our side (I believe).

China got the bomb, but have no fears,

They can't wipe us out for at least five years.

Who's next?

Then Indonesia claimed that they

Were gonna get one any day.

South Africa wants two, that's right:

One for the black and one for the white.

Who's next?

Egypt's gonna get one too,

Just to use on you know who.

So Israel's getting tense.

Wants one in self defense.

"The Lord's our shepherd," says the psalm,

But just in case, we better get a bomb.

Who's next?

Luxembourg is next to go,

And (who knows?) maybe Monaco.

We'll try to stay serene and calm

When Alabama gets the bomb.

Who's next?

Who's next?

Who's next?

Who's next?

"Tom Lehrer: Who's Next, 1967 - Educational Video." Tom Lehrer: Who's Next, Humorous Song. Nuclear Proliferation, Video, Elearning. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2014

Article - The Heritage Foundation

Nuclear proliferation endangers world stability

By Bob Graham and Jim Talent

During the first presidential debate in 2004, President Bush and Sen. John Kerry agreed -- as stated by the president -- that "the single, largest threat to American national security today is nuclear weapons in the hands of a terrorist network." Yet despite that consensus, the subject of weapons of mass destruction proliferation has quickly disappeared from the national agenda.

Few comments or questions on this issue have been posed to the presidential candidates, even though preventing WMD proliferation should be on the short list of priorities for a McCain or Obama White House. And it rarely appears on polls of the most urgent concerns of citizens. So, in 2008, after seven years in which there have been no successful terrorist attacks inside the country, why not relax? Here are the reasons:

Terrorists have continued to demonstrate the intent to acquire a WMD capability. As Director of National Intelligence Admiral Michael McConnell said in his Sept. 10, 2007, testimony to the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, "al Qaeda will continue to try to acquire and employ chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear material in attacks and would not hesitate to use them if it develops what it deems is sufficient capability."

The potential human toll of an attack utilizing weapons of mass destruction is appalling. On a normal workday, half a million people crowd the area within a half-mile radius of Times Square. A noon detonation of a nuclear device in Midtown Manhattan would kill them all.

Another attack -- particularly with WMD -- would have a devastating impact on the American and the world economies. As former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan warned, a nuclear terrorist attack would push "tens of millions of people into dire poverty," creating "a second death toll throughout the developing world."

The environment for the use of nuclear and biological weapons has changed. Although Russia is doing a better job of securing its stockpiles and therefore is less of a threat, North Korea and Iran have taken its place. North Korea has gone from two bombs worth of plutonium to an estimated ten. Iran has gone from zero centrifuges spinning to more than 3,000.

In what some have termed a "nuclear renaissance," many nations are now seeking commercial nuclear power capacity that will add to the inventory of nations and scientists who could extend their interest to nuclear weapons.

With the nuclear surprises we've experienced in Iran, Syria and North Korea, it is clear that current nonproliferation regimes and mechanisms can no longer be certain to prevent more nuclear proliferation or the theft of bomb-usable materials.

Biologists are creating synthetic DNA chains of diseases which have been considered extinct, such as the 1918 influenza virus that killed over 40 million people. The potential of using these laboratory-developed strains against an unaware and noninoculated population is ominous.

There is the necessity of engaging the American people. Unlike the Cold War, which was a superpower vs. superpower confrontation, the current asymmetric threat that would be dramatically escalated if the terrorists had access to nuclear or biological weapons. The incorrect claims regarding Saddam Hussein's WMD and his collusion with al Qaeda have contributed to public skepticism. Nonetheless, there was and is a real danger that al Qaeda will get a nuclear bomb and attack an American city.

Faced with the possibility of a mushroom cloud over Manhattan, many people are paralyzed by a combination of denial and fatalism. The president is the best position to rally the resilience and patriotism of Americans to this threat.

We have been asked by Congress to lead a bipartisan commission to assess the current state of our nation's policies to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction into the hands of rogue states and nonstate terrorists. Our final report will be released in November. Based on our assessment, we will make recommendations to the new Congress and the new president.

We trust that the president and Congress will recognize the primacy of this threat and the consequences should it come to pass. Nuclear terrorism has been described as the ultimate avoidable catastrophe. Whether it -- and other WMD catastrophes -- will be avoided will depend in large part on where it ranks among the 44th president's priorities.

Bob Graham, a former U.S. senator from Florida, is chairman of the congressionally established Commission on the Prevention of WMD Proliferation and Terrorism and the board of oversight of the Graham Center for Public Service at the University of Florida and the University of Miami. Jim Talent a former U.S. senator from Missouri, is vice chairman of the WMD Commission and Distinguished Fellow at the Heritage Foundation.

First appeared in the Miami Herald

"Nuclear Proliferation Endangers World Stability." The Heritage Foundation. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2014.

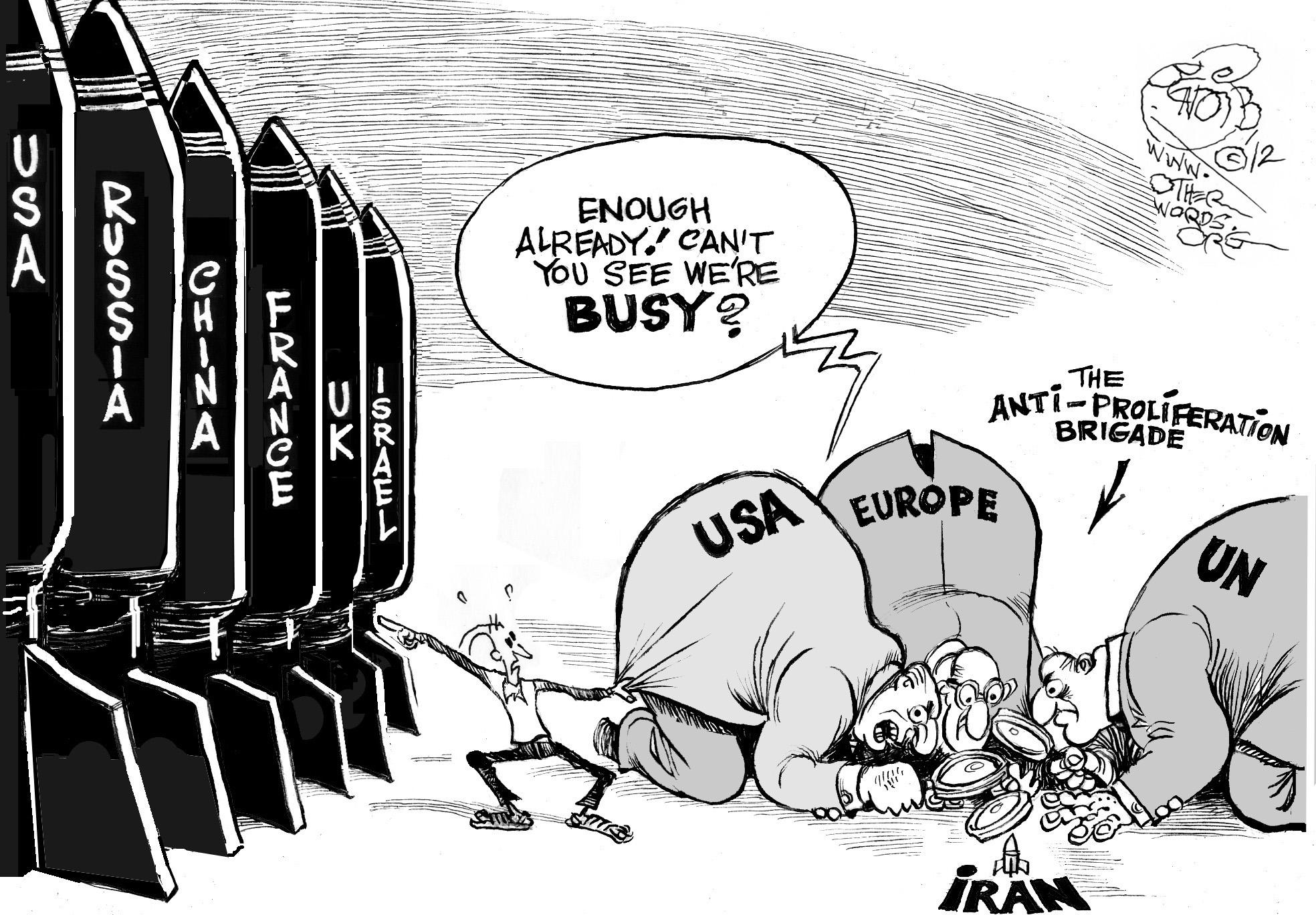

Political Cartoon - "Anti-proliferation Brigade" by Khalil Bendib

Google Image